Review: 40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat

Posted by FlagsNZ,

Several LEGO sets will become available on Friday as part of LEGO's Black Friday releases.

So, from Friday, 10335 The Endurance will be available. While stocks last, 40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat will be a Gift With Purchase.

Read on as I review Shackleton's Lifeboat with a continuation of the fascinating survival story and the role this lifeboat played.

Summary

40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat, 232 pieces.

This is an almost essential companion set to 10335 The Endurance

- Celebrates Shackleton's amazing journey of survival

- Nice tidy build of an iconic small boat

- Missing some key minifigures

- Should be more widely available

The set was provided for review by LEGO. All opinions expressed are those of the author.

If you haven't read it, Part 1 of this survival story is embedded in my review of 10335 The Endurance.

Researching for this review

As mentioned in the review for 10335 The Endurance, I have sourced information for this review primarily from three books:

-

Endurance - The true story of Shackleton's incredible voyage to the Antarctic by Alfred Lansing,

-

South - The Endurance expedition written by Sir Ernest Shackleton, and

-

Chasing Shackleton - Re-Creating the World's Greatest Journey of Survival by Tim Jarvis

I have also sourced information from several websites and have included hyperlinks to those sources in this review.

For the younger reader, Shackleton's Journey by William Grill is an award-winning Illustrated children's book which comes highly recommended.

Webpages or eBooks

You can also download and read about Shackleton's story of survival on either of these two webpages or eBooks:

-

The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition written by Caroline Alexander

-

South: The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition written by Sir Ernest Shackleton

The build

This has been a collaborative effort. 40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat was sent to Brickset Towers and Huw has therefore taken all the images for this review.

40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat has 232 pieces.

It starts by assembling the sledge, a crate of equipment, and a small brick-built stove.

On October 29, 1915, Shackleton (1919, p. 89) records:

. . . All hands this morning were busy preparing our gear, fitting the boats on sledges to carry the boats . . . The main motor sledge, with a little fitting from the carpenter, carried our largest boat admirably. For the next boat, four ordinary sleds were lashed together, but we were dubious as to the strength of this contrivance, and as a matter of fact, it broke down quickly under strain . . .

Shackleton (1919, p. 92) goes on to say:

The boats, with their gear and the sledges beneath them, weighed each more than a ton. The cutter was smaller than the whaler, but weighed more and was a much more strongly built boat. The whaler was mounted on the sledge part of the Girling tractor forward and two sledges amidships and aft. These sledges were strengthened with cross timbers and shortened oars fore and aft. The cutter was mounted on the aero sledge. The sledges were the point of weakness. It appeared almost hopeless to prevent them smashing under their heavy loads when travelling over rough pressure ice which stretched ahead of us for probably 300 miles.

Lansing (2000, p.63) states:

McNeish and McLeod began mounting the whaler and one of the cutters onto sledges. The boats, with their sledges, would weigh more than a ton apiece, and nobody had any delusions that it would be easy to drag them over the chaotic surface of the ice with its pressure ridges occasionally two stories high.

Lansing (2000, p. 74) describes McNeish's workmanship:

As a ship's carpenter, McNeish was a master craftsman. Nobody ever saw him use a ruler. He simply studied a job briefly, then set to work sawing the proper pieces - and they always fitted exactly.

Endurance's lifeboats

Shackleton's lifeboat represents the James Caird, a double-ended whaler that was built specially for this expedition to Frank Worsley's design.

Jarvis (2013, p. 42) describes James Caird's design and construction:

The James Caird was built in July 1914 by W. & J. Leslie, boat builders of Coldharbour Lane, near West India Docks in London.

Commissioned by Frank Worsley, her skipper, and completed to his exact specifications, she was a double-ended whaler, with carvel planking of Baltic pine. This created a flush outer surface as opposed to clinker planking, where planks overlap. Her stem and stern posts were English oak.

Endurance had four lifeboats that were secured to the ship using radial davits. The two cutters were stowed on the forward two davits; the James Caird was located on the starboard aft davit; and a fourth, smaller, motor lifeboat was located on the port aft davit.

Three of Endurance's four lifeboats were salvaged for the next phase of the survival journey.

These three lifeboats did not receive their names until 28 November 1915, a week after the Endurance had sunk.

Lansing (2000, p. 87) notes:

Preparations were being completed for the 'journey to the west.' The boats were as ready as McNeish could make them. Nothing remained except to name them, and Shackleton did so.

Accordingly, the whaler was christened James Caird; the No. 1 cutter became the Dudley Docker, and the second cutter, the Stancomb Willis.

George Marston, the artist, got busy with what remained of his paints and lettered the proper name on each boat.

Shackleton (1919, p. xviii) mentions his principal financial backers for this expedition:

I must particularly refer to the munificent donation of £24,000 from the late Sir James Caird, and to one of £10,000 from the British Government. I must also thank Mr. Dudley Docker, who enabled me to complete the purchase of the Endurance, and Miss Elizabeth Dawson Lambton, who since 1901 has always been a firm friend to Antarctic exploration, and who again, on this occasion, assisted largely.

The Royal Geographical Society made a grant of £1000; and last, but by no means least, I take this opportunity of tendering my grateful thanks to Dame Janet Stancomb Wills, whose generosity enabled me to equip the Endurance efficiently, especially as regards boats (which boats were the means of our ultimate safety), and who not only, at the inception of the Expedition, gave financial help, but also continued it through the dark days when we were overdue, and funds were required to meet the need of the dependents of the Expedition.

To compare these amounts to today's values:

-

£24,000 in 1914 is equal to £3.5M, $4.5M, €4.2M in 2024

-

£10,000 in 1914 is equal to £1.4M, $1,9M, €1.7M in 2024

-

£1,000 in 1914 is equal to £0.14M, $0.19M, €0.17M in 2024

40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat

When complete, Shackleton's Lifeboat sits on a sledge. You can see her two masts. The lifeboat is rigged as a ketch: the aft (mizzen) mast is stepped in front of the rudder.

The boat is covered by a deck and has two oars clipped to this deck.

The bulk of the interior of the Lifeboat is occupied with SNOT bricks that enable the curved bricks on the sides to be attached. There is no room in the boat's cabin for the minifigures.

Lansing (2000, p.80) describes the work undertaken to modify the boats:

Old Chippy McNeish, usually assisted by McLeod, How, and Bakewell, spent these days raising the sides of the whaler and one of the cutters to make them as seaworthy as possible. However, they were hampered by a shortage both of tools and materials. Only a saw, a hammer, a chisel, and a adze had been salvaged. And Mcneish had obtained his few nails by pulling them one by one out of the superstructure of the Endurance.

Lansing (2000, p.85) adds:

The task of raising the whaler's sides was almost complete and everyone was impressed with the job Mcneish had done. The shortage of tools and lack of materials seemed not to have handicapped him in the least. To calk the planks he had added, he had been forced to resort to cotton lamp wick and the oil colours from Marston's artist's box.

Jarvis (2013, p. 42) comments about the James Caird:

. . . she really only became the James Caird we know from Shackleton's journey after the phenomenal efforts of Harry 'Chippy' McNeish, carpenter on the Endurance and a 'splendid shipwright.' Helped by others among the crew after Shackleton and his men took to the ice, McNeish raised her gunwales by some thirty-five centimetres (14 inch), using wood salvaged from the Endurance's by-now defunct motorboat, and nails from the Endurance herself.

Shackleton knew very early on that they would have to undertake a sea voyage at some point, so he had McNeish construct whalebacks at each and fit a pump made by photographer Frank Hurley from the casing of the ship's compass. It was something that would prove invaluable in the journey ahead.

Shackleton (1919, p. 177) Text

There was a lull in the weather on April 21 [1916], and the carpenter started to collect material for the decking of the James Caird. He fitted the mast of the Stancomb Wills fore and aft inside the James Caird as a hog-back and thus strengthened the keel with the object of preventing our boat "hogging" - that is, buckling in heavy seas. He had not sufficient wood to provide a deck, but by using the sledge runners and box lids he made a framework extending from the forecastle to the well. It was a patched-up affair, but it provided a base for a canvas covering.

As mentioned in my previous review, Lansing describes in detail the three named lifeboats:

The Dudley Docker and the Stancomb Wills were cutters - heavy-square sterned boats of solid oak. Their Norwegian builders called them 'bottlenose killer,' boats or dreperbats because they were originally designed for hunting bottle-nosed whales.

They were 21 feet 9 inches long (6.6 m) long, with a 6-foot-2-inch beam (1.9 m) and they had three seats or thwarts, plus a small decking in the bow and in the stern.

The James Caird was a double-ended whale boat, 22 feet 6 inches (6.9 m) long and 6 feet 3 inches wide (1.9 m). She had been built in England to Worsley's specifications of Baltic pine planking over a framework of American elm and English oak. Though she was somewhat larger than the other two, she was a lighter, springier boat because of the materials from which she was built (Lansing, 2000, p. 145).

Planks and frames from the motor lifeboat were used to raise the sides of the James Caird and the Dudley Docker.

Naming Endurance's boats

You can see in the three images (below) the names given to the three lifeboats salvaged from Endurance. Note that James Caird has actually been named J Caird. I suspect that they must have run out of paint!

The fact that the boats were christened with the names of the principal financial backers for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition indicates to me that Endurance was not a registered ship.

Had Endurance been 'registered' then her lifeboats would have been named for the parent ship and would have been assigned numbers. Endurance would also have had a Port of Registry carved into her stern.

This gives me more confidence that Endurance was a private yacht affiliated with the Royal Clyde Yacht Club and, therefore, this is the reason she flew the Blue Ensign of that yacht club.

The completed model

The completed model comes with the James Caird sitting on its sledge, a crate of supplies and tools, a small stove and one of Hurley's cameras on a tripod. Shackleton and Hurley look on.

Here is a close up view of the crate of supplies and tools and the small brick-built stove.

Shackleton (1919, p. 96) describes the stove and its effectiveness:

The collection of food was now the all-important consideration. As we were to subsist entirely on seals and penguins, which were to provide fuel as well as food, some form of blubber stove was a necessity. This was eventually very ingeniously contrived from the ship's steel ash shoot, as our first attempt with a large iron oil drum did not prove eminently successful. We could only cook seal or penguin hooshes or stews on this stove, and so uncertain was its action that the food was either burnt or only partially cooked; and, though hungry as we were, half-raw seal meat was not very appetising.

Lansing (2000, pp.79-80) describes the daily routine and the operation of this stove:

Each day in camp began at 6:30 A.M., when the night watchman drew off a tablespoon of gasoline from a drum in the galley and poured it into a small iron saucer in the bottom of the stove. He then lighted the gasoline and it, in turn, ignited strips of blubber draped on grates above the saucer. Hurley had fashioned the stove from an old iron drum and a cast-iron ash chute taken from the ship.

How Shackleton's Lifeboat has been assembled is a fusion of her two configurations:

-

James Caird was mounted onto the sledge for transport over the ice but wasn't covered in during that phase.

-

The timber used to raise the sides of the Dudley Docker was repurposed at Elephant Island to fashion the decking over the James Caird (Lansing, 2000, p.190).

Lansing (2000, p. 149) describes the sail rigs of the three boats:

The [James] Caird was fitted with two masts for a main and a mizzensail, plus a small jib in the bow. The [Dudley] Docker carried a single lug sail, and the [Stancomb] Wills mounted only a very small mainsail and jib. The boats were thus hardly fit sailing companions - and this fact immediately became apparent when the sails were set. The Caird caught the wind and heeled to port, drawing steadily ahead of the other two boats. Though the Docker was somewhat faster than the Wills, the difference was slight, and neither boat could sail into the wind. There was nothing for the Caird to do but to hang back so as not to outdistance the others.

The image below shows Shackleton's Lifeboat off the sledge and the deck cover removed. You can see two thwarts (a seat extending athwart (across) a boat).

When the deck cover is in place there remains a small opening where the helmsman would have sat to steer the boat. See the explanation (below) of yoke lines as the tiller would have pivoted on the mizzen (aft) mast. Yoke lines connected the tiller to the rudder.

Lansing (2000, p.224) describes steering James Caird during the voyage to South Georgia:

The man at the helm, of course, suffered the most, and each of them took his turn at the yoke lines [emphasis added] for an hour and twenty minutes during each watch. But the other two men on duty were better off by comparison.

This link takes you to an image that shows you a typical navy whaler and the steering arrangement with yokes and yoke lines. The tiller is located where the mizzen mast was stepped.

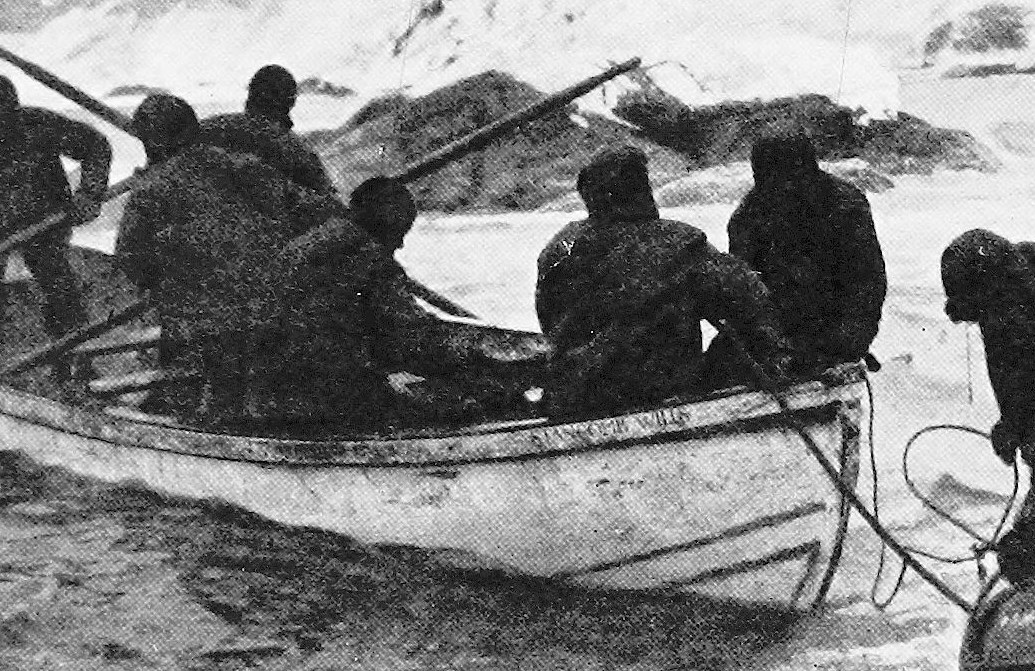

The image below shows James Caird being pulled along by a team of men.

Lansing (2000, p. 66) describes this scene:

The boats, drawn by fifteen men harnessed in traces under Worsley's command, were the last. It was killing toil. Because of their weight, the boats sank into the soft surface of the snow. To move them, the men in the traces had to strain forward, at times leaning nearly parallel with the ground, and the whole operation was more like ploughing through snow than sledging.

The real James Caird

The James Caird was returned to England in 1919. On 5 January 1922, Shackleton died suddenly of a heart attack, while the expedition's ship Quest was moored at South Georgia.

Later that year John Quiller Rowett, who had financed the Quest expedition and was a former school friend of Shackleton's from Dulwich College, South London, decided to present the James Caird to the college. It remained there until 1967, although its display building was severely damaged by bombs in 1944.

It was returned to Dulwich College and placed in a new location in the North Cloister, on a bed of stones gathered from South Georgia and Aberystwyth. This site has become the James Caird's permanent home, although the boat is sometimes lent to major exhibitions.

Minifigures

40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat comes with two minifigures: Frank Hurley and Ernest Shackleton.

The two minifigure heads have been seen before:

-

Hurley's head has appeared in two sets.

-

Shakleton's head has been seen in one other set.

The torso of Hurley has been seen before in two other sets.

The torso of Shackleton has been seen before in two other sets.

Shackleton is wearing a dark brown fedora hat that has been seen in four other sets.

The inspiration for these two minifigures may have come from the image below. It shows Ernest Shackleton and Frank Hurley sitting outside their tent at Ocean Camp.

The rear image of the two torsos.

Shackleton holds a marine sextant in dark stone grey.

There were two sextants carried in James Caird during its voyage to South Georgia, although it was Frank Worsley who undertook all the navigation.

Sextant derives its name from the fact that it is one-sixth of a circle. The principle of the sextant is that it can measure angles up to 120° - twice the 60° rotation of the index mirror.

This was me using my father's sextant during a "bucket list" voyage in the replica HMB Endeavour voyage of 2019. You can see more of this voyage in my review of 10210 Imperial Flagship.

I am a second-generation Master Mariner. I would also like to take another opportunity to post a shoutout to my father, Capt. Jim Wardle.

My father won the sextant in the above image when he was a cadet in HMS Conway in 1954. This image (below) is Jim Wardle aboard mv Crusader in the late 1950s using his sextant.

Sixty years separate these two images.

Frank Hurley

Frank Hurley's photographic kit for the expedition included the cinematograph machine, plate still camera and several smaller Kodak cameras, along with various lenses, tripods, and developing equipment, most of which had to be abandoned with the loss of their ship Endurance in 1915.

He kept only a hand-held Vest Pocket Kodak camera and three rolls of film and, for the rest of the expedition, he shot just 38 images.

The image below shows Frank Hurley on the ice floe and gives an indication of the size of his camera when viewed next to the bow of Endurance.

Lansing (2000, p. 70) comments on the recovery of some of Frank Hurley's negatives:

How and Bakewell, whose quarters in the forecastle, were hopelessly submerged, went treasure-hunting elsewhere. Carefully making their way along a passageway below, they passed the door of the compartment Hurley used as a darkroom. Looking in, they saw the cases containing Hurley's photographic negatives. After hesitating a moment, the two seamen squeezed past the half-jammed door, stepped into the ankle-deep water, and grabbed the cases off the shelves. It was a great treasure, and they returned the negatives to Hurley that night.

It is remarkable how close we came to losing this valuable photographic record of this amazing journey!

Missing minifigures

The story of James Caird - Shackleton's lifeboat - involves many people, but two members of the expedition require a special mention:

-

Frank Worsley, and

-

Harry "Chippy" McNeish.

(Note Harry McNeish is sometimes referred to as Henry McNish)

Frank Worsley

Like this reviewer, Frank Worsley was a New Zealand citizen, a Master Mariner and an officer in the Royal Naval Reserve.

He played a vital role in the navigation and boat handling during this ill-fated expedition.

Frank Worsley secured the vital ship's chronometer. Lansing (2000, p. 160) comments:

A hundred times, it seemed, Worsley was asked what time it was. Each time, he reached under his shirt and took out the chronometer he carried slung around his neck to keep it warm. Holding it up close to his face, he read its hands in the feeble light of the moon, shining through the thin snow clouds.

Lansing (2000, p. 194) explains Worsley's commitment to safeguarding the essential navigation equipment:

Worsley had gathered together all the navigation aids he could find. He took his own sextant and another which belonged to Hudson, along with the necessary navigation tables and what charts were to be had. These were packed into a box that was made as watertight as possible. He carried his sole chronometer slung around his neck. Out of twenty-four on board the Endurance when she sailed from England, this one alone had survived.

There is an unchallengeable connection between time and navigation. This is evident in the twenty-first century by the inclusion of several atomic clocks aboard every global navigation satellite.

It comes as no surprise to me that one of the new sets that will be available in the Rewards Centre from Black Friday, 29th November is 5009045 Chronometer. I am sure this is another link to 10335 The Endurance.

Lansing (2000, p, 157) comments on the struggle of taking sextant sights in Dudley Docker during the voyage towards Elephant Island:

About ten-thirty, Worsley took out his sextant, Then, bracing himself against the mast of the [Dudley] Docker, he carefully took his sight - the first since leaving Patience Camp. At noon, he repeated the procedure, as the boats lay awaiting the result. Every face was turned towards Worsley as he sat in the bottom of the Docker working out his figures. They watched to see his expression when the two lines of position were plotted for a fix. It took him much longer than usual, and gradually a puzzled look came over his face. He checked his calculations over, and the expression of puzzlement gave way to one of worry. Once more he ran through his computations, and then he slowly raised his head. Shackleton had brought the [James] Caird alongside the Docker, showed him the position. - 62° 15' South, 53° 7' West.

They were 124 miles due east of King Island - 22 miles further away from land than they had been when they launched the boats from Patience Camp three days before!

Lansing (2000, p. 171) sums up Worsley's stature in the team and its eventual survival:

They had been in the boats for now for five and a half days, and during that time almost everyone had come to look upon Worsley in a new light. In the past he had been thought of as excitable and wild - even irresponsible. But all that had changed now. During these past days he had exhibited an almost phenomenal ability, both as a navigator and in the demanding skill of handling a small boat. There wasn't another man in the party even comparable with him, and he had assumed an entirely new stature because of it.

Harry "Chippy" McNeish.

Throughout these two reviews, I have mentioned the various ways in which Harry McNeish's contribution led to the ultimate survival of his fellow crew members. There is one more item that I want to add.

Shackleton (1919, p. 213) describes McNeish's last great contribution to the success of their perilous journey:

I had given away my heavy Burberry boots on the ice floe, and had now a comparatively light pair in poor condition. The carpenter assisted me by putting several screws in the sole of each boot with the object of providing a grip on the ice. The screws came from the James Caird.

Lasing (2000, p. 262) adds to this description:

May 16 [1916], dawned cloudy and rainy, keeping them confined under [James] Caird nearly all day. They spent the time discussing the journey and McNeish busied himself fixing their boots for climbing. He had removed four dozen 2-inch screws from the Caird, and he fixed eight of them into each shoe to be worn by the members of the overland party.

So, all the way through, McNeish 's contribution was essential to the overall survival and success of the whole group of men.

Polar Medal

The Polar Medal is a medal awarded by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom to individuals who have outstanding achievements in the field of polar research, and particularly for those who have worked over extended periods in harsh climates. It was instituted in 1857 as the Arctic Medal, and renamed the Polar Medal in 1904.

Earlier this year, Ernest Shackleton's Polar Medals arrived in New Zealand and were gifted to the Christchurch Museum.

McNish had briefly rebelled earlier in the journey, refusing to take his turn in the sledge harness and protesting to Frank Worsley that, since the Endurance had been destroyed, the crew was no longer under any obligation to follow orders.

Whatever the true story of the rebellion on the ice, neither Worsley nor McNeish ever mentioned the incident in writing. Shackleton omitted it entirely from South, his account of the expedition, and referred to it only tangentially in his diary: "Everyone working well except the carpenter. I shall never forget him in this time of strain and stress".

Despite McNish's efforts in preparing and sailing on the James Caird voyage, his prior insubordination meant that, on Shackleton's recommendation, he was one of four men denied the Polar Medal.

The others whose contributions fell short of Shackleton's expected standards were John Vincent, William Stephenson and Ernest Holness.

There have been several attempts for Harry McNeish's Polar Medal to be awarded posthumously.

The story of Mrs Chippy

Mrs Chippy, a tiger-striped tabby, was taken on board the ship used by the expedition's Weddell Sea party, Endurance, as a ship's cat by carpenter and master shipwright Harry "Chippy" McNish ("Chippy" being a colloquial British term for a carpenter).

The cat acquired its name because, once aboard, it followed McNish around like an overly attentive wife.

One month after the ship set sail for Antarctica, it was discovered that, despite its name, Mrs Chippy was actually a male. By that time, however, the name had stuck.

He was described as "full of character" by members of the expedition and impressed the crew with his ability to walk along the ship's inch-wide rails in even the roughest seas.

Mrs Chippy on the shoulder of crew member Perce Blackborow.

Scottish-born Harry McNeish is buried in the Karori Cemetery in Wellington, New Zealand.

His grave went unmarked until the New Zealand Antarctic Society (NZAS) erected a headstone in 1959. They added a bronze statue of his beloved cat, Mrs Chippy, in 2004.

Mrs Chippy came to a sad end during the voyage of Endurance. This affected Harry McNeish for the rest of his life.

Verdict

This is a nice model of an iconic small boat that has an unparalleled place in history.

This model is an almost essential component of the parent ship 10335 The Endurance. Its limited supply as GWP will quickly dry up.

I believe that Frank Worsley and Harry McNeish should have also been included as minifigures; they both played a pivotal role in the success of James Caird component of the survival journey.

If Harry McNeish were included, then his companion cat could also have been included. Mrs Chippy occupies a special place in feline nautical history.

References

Alexander, C., n.d. The Endurance: Shackleton's Legendary Antarctic Expedition. Retrieved from https://erenow.org/biographies/the-endurance-shackletons-legendary-antarctic-expedition/

Javis, T., 2013. Chasing Shackleton - Re-Creating the World's Greatest Journey of Survival. London: William Morrow & Company

Lansing, A., 2000. Endurance - The true story of Shackleton's incredible voyage to the Antarctic. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Shackleton, E., 1919. South - The Endurance expedition. London: William Heinemann

Shackleton, E., 2021. South - The Story of Shackleton's Last Expedition. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5199

Thanks Huw, for the fabulous images that were taken for this review.

132 likes

28 comments on this article

Great review @FlagsNZ . I'll certainly be getting this.

This set IMO, is the third best GWP of this year, behind the Star Wars ones.

Thank you so much for the amazing review with such a large amount of historical research!

Another classic, the review more so than the boat. Nevertheless, it is nice add on to a fairly reasonable set.

The review, the set, the price, the GWP, the lack of other good Lego deals, it all argues for a Day 1 purchase.

It'll go great with my mint candle (if ya know, ya know).

I think more than two minifigs is a bit much for a free set. Although, Mrs Chippy should have been included.

I appreciate rich historical information but it would be easier for readers if text of review would be in one block and then additional information below. So everyone choose what to read and on what focus.

Definitely going to get this and the Endurance.

As for missing minifigures and cat, I'm sure they could be moc from bricks and pieces.

A fantastic review and brilliantly researched, thank you! I shall be staying up tonight to get the Endurance and this GWP as I don't want to risk missing out on my own model of the John Caird.

I'm also now genuinely considering a long dreamed-for change of career into the merchant navy thanks to your clear love of ships!

Outstanding review!

@Maxbricks14 said:

"Great review @FlagsNZ . I'll certainly be getting this.

This set IMO, is the third best GWP of this year, behind the Star Wars ones."

What about 40712?

wheres the cat minifig? :(

Wow, that has to be a record for review words per part in the set ;-)

Great story again.

From my own reading up on Shackleton, I though McNeish's rebellion was over the shooting of Mrs Chippy. For the rest of his life, he never forgave Shackleton for that.

For all his brilliant leadership and decisions, I think that was his worst moment of the trip. I understand the reasoning, but I think the few sardines per day to keep the cat alive would have been worth it for crew morale.

About the model, I thought when I built it that the bow is too wide. A centre of only one stud wide would look better. Which of course would affect the rest of the design... Also, I understand what the two wires along the outside represent, but the way they are held by the handlebars at the front just looks a bit... strange.

I know the GnR song is “Shackler’s Revenge” but for some reason I keep thinking of this set as “Shackleton’s Revenge.”

Realy great review! Hope to see more reviews like thata!

So, how the cat died? Was Mrs (Mr) Chippy really killed by Shackleton???

Awesome review, again. The level of research is incredibly well done. You should seriously write a book or something on the historical context of historical Lego sets.

@Videofronta said:

"So, how the cat died? Was Mrs (Mr) Chippy really killed by Shackleton???"

Mrs Chippy was a boy, yes.

From Shackleton's diary:

"This afternoon Sallie's three youngest pups, Sue's Sirius, and Mrs. Chippy, the carpenter's cat, have to be shot. We could not undertake the maintenance of weaklings under the new conditions. Macklin, Crean, and the carpenter seemed to feel the loss of their friends rather badly."

Regardless of the reasons, I think if someone shot my cat dead, I'd be a very very annoyed crew member. McNeish's attitude has a rather understandable origin, maybe.

Fantastic review and well researched! A very informative and enjoyable read. I'm looking forward to picking this set up tonight; probably my first Day-1 must buy in a very long time!

I'm not sure how to feel about this review, On the one hand, it was a very well-researched and entertaining read. On the other hand, it made me regret not having the space for 10335 even more!

@Duq:

If you really dig into exactly what these men went through, by all rights the histories should have ended with “and they were never seen again.” It’s half-miracle, half being able to plot the absolute best course of action, and probably a few dashes of pure stubbornness that kept every single (human) member of the expedition alive. Cruel as it may have seemed, the cat was eating better than the people, and Shackleton would have absolutely been weighing the cost of losing one or more of his crew’s lives against keeping the cat.

@Videofronta:

We know that Shackleton ordered that four dogs and the cat be shot. I don’t think it was recorded who actually pulled the trigger, and any witnesses to the deed are long dead.

And Mrs. Chippy was named before they realized the cat was male. Not sure how they could have missed something as obvious as that, considering how frequently cats walk with their tails raised vertical.

@maffyd:

So there’s a huge controversy that resulted from that one command. I agree that McNeish probably bucked Shackleton’s authority over that one incident, but it’s kind of like waiting until you’re halfway between the last camp and the peak of Everest to get in an argument. If there’s legitimate reason to believe the person in charge is about to get everyone killed, that’s one thing. If it’s because you felt he was unnecessarily mean, suck it up, buttercup. Wait until you’re safe to have that fight.

Shackleton specifically requested that three members of the expedition be denied the Polar Medal, and McNeish was one of the three. Clearly he was a critical component in the survival of the entire crew, but his little rebellion never sat right with Shackleton. There’s a movement to get his medal awarded posthumously, but then you really need to consider whether or not Shackleton made the right call in that moment, when the fate of every member of his crew was in serious question. You can’t look at it from our perspective, knowing that they all made it back safely, because they may have all expected to die. Shooting the animals may have just felt like an added bit of cruelty heaped on their looming fate.

Also, once they’re out on open water, and the cat’s safety comes into question, would the men have been able to make the hard choice, or would they have gotten other people, perhaps themselves, killed in an attempt to save the cat? Keep in mind that this is a cat who leapt out of a porthole into open water on the outbound trip. And the man at the helm turned the ship around and they spent over ten minutes rescuing him from the water. Shackleton had to be focused on the survival of his crew, but it seems they might have had a hard time if they were forced to choose between the cat and another crewmate.

40729 Shackleton's Lifeboat already gone on USA shop!

Your "reviews" are amazing. Such a story behind so a little Lego set. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and passions. Simply excellent and interesting to read.

@PurpleDave said:

" @Duq :

If you really dig into exactly what these men went through, by all rights the histories should have ended with “and they were never seen again.” It’s half-miracle, half being able to plot the absolute best course of action, and probably a few dashes of pure stubbornness that kept every single (human) member of the expedition alive. Cruel as it may have seemed, the cat was eating better than the people, and Shackleton would have absolutely been weighing the cost of losing one or more of his crew’s lives against keeping the cat.

@Videofronta :

We know that Shackleton ordered that four dogs and the cat be shot. I don’t think it was recorded who actually pulled the trigger, and any witnesses to the deed are long dead.

And Mrs. Chippy was named before they realized the cat was male. Not sure how they could have missed something as obvious as that, considering how frequently cats walk with their tails raised vertical.

@maffyd :

So there’s a huge controversy that resulted from that one command. I agree that McNeish probably bucked Shackleton’s authority over that one incident, but it’s kind of like waiting until you’re halfway between the last camp and the peak of Everest to get in an argument. If there’s legitimate reason to believe the person in charge is about to get everyone killed, that’s one thing. If it’s because you felt he was unnecessarily mean, suck it up, buttercup. Wait until you’re safe to have that fight.

Shackleton specifically requested that three members of the expedition be denied the Polar Medal, and McNeish was one of the three. Clearly he was a critical component in the survival of the entire crew, but his little rebellion never sat right with Shackleton. There’s a movement to get his medal awarded posthumously, but then you really need to consider whether or not Shackleton made the right call in that moment, when the fate of every member of his crew was in serious question. You can’t look at it from our perspective, knowing that they all made it back safely, because they may have all expected to die. Shooting the animals may have just felt like an added bit of cruelty heaped on their looming fate.

Also, once they’re out on open water, and the cat’s safety comes into question, would the men have been able to make the hard choice, or would they have gotten other people, perhaps themselves, killed in an attempt to save the cat? Keep in mind that this is a cat who leapt out of a porthole into open water on the outbound trip. And the man at the helm turned the ship around and they spent over ten minutes rescuing him from the water. Shackleton had to be focused on the survival of his crew, but it seems they might have had a hard time if they were forced to choose between the cat and another crewmate."

I agree with your comment on Mrs. Chippy and 'his' fate. Mrs. Chippy played a sentimental role and at that stage in their survival journey Shackleton wasn't interested in any sentimentality. That being said, Shackleton was somewhat uncaring and could have delayed the decision to have Mrs. Chippy put down.

As for the issue of the Polar Medal, Shackelton and his entire crew made it back safely and t\Harry McNish played a pivotal role in that success. Shackleton could have absolved him of his prior insubordination but chose not to. This says more about Shackleton's character as denying McNish his Polar Medal seems vindictive.

It is all too easy to criticize these actions when viewed 100 years later sitting in comfort.

@Brick_t_ :

Thank you for your comment. I really enjoyed linking these two sets with the fantastic wealth of history that exists from this expedition.

@FlagsNZ:

It sounds like McNeish never forgave Shackleton for ordering the death of the cat. We don't know much about what went on between them during the entire trip from where the Endurance sank to where they finally made it back to civilization. I don't think Shackleton's character is the only one that might need to be questioned.

@FlagsNZ said:

" @PurpleDave said:

" @Duq :

If you really dig into exactly what these men went through, by all rights the histories should have ended with “and they were never seen again.” It’s half-miracle, half being able to plot the absolute best course of action, and probably a few dashes of pure stubbornness that kept every single (human) member of the expedition alive. Cruel as it may have seemed, the cat was eating better than the people, and Shackleton would have absolutely been weighing the cost of losing one or more of his crew’s lives against keeping the cat.

@Videofronta :

We know that Shackleton ordered that four dogs and the cat be shot. I don’t think it was recorded who actually pulled the trigger, and any witnesses to the deed are long dead.

And Mrs. Chippy was named before they realized the cat was male. Not sure how they could have missed something as obvious as that, considering how frequently cats walk with their tails raised vertical.

@maffyd :

So there’s a huge controversy that resulted from that one command. I agree that McNeish probably bucked Shackleton’s authority over that one incident, but it’s kind of like waiting until you’re halfway between the last camp and the peak of Everest to get in an argument. If there’s legitimate reason to believe the person in charge is about to get everyone killed, that’s one thing. If it’s because you felt he was unnecessarily mean, suck it up, buttercup. Wait until you’re safe to have that fight.

Shackleton specifically requested that three members of the expedition be denied the Polar Medal, and McNeish was one of the three. Clearly he was a critical component in the survival of the entire crew, but his little rebellion never sat right with Shackleton. There’s a movement to get his medal awarded posthumously, but then you really need to consider whether or not Shackleton made the right call in that moment, when the fate of every member of his crew was in serious question. You can’t look at it from our perspective, knowing that they all made it back safely, because they may have all expected to die. Shooting the animals may have just felt like an added bit of cruelty heaped on their looming fate.

Also, once they’re out on open water, and the cat’s safety comes into question, would the men have been able to make the hard choice, or would they have gotten other people, perhaps themselves, killed in an attempt to save the cat? Keep in mind that this is a cat who leapt out of a porthole into open water on the outbound trip. And the man at the helm turned the ship around and they spent over ten minutes rescuing him from the water. Shackleton had to be focused on the survival of his crew, but it seems they might have had a hard time if they were forced to choose between the cat and another crewmate."

I agree with your comment on Mrs. Chippy and 'his' fate. Mrs. Chippy played a sentimental role and at that stage in their survival journey Shackleton wasn't interested in any sentimentality. That being said, Shackleton was somewhat uncaring and could have delayed the decision to have Mrs. Chippy put down.

As for the issue of the Polar Medal, Shackelton and his entire crew made it back safely and t\Harry McNish played a pivotal role in that success. Shackleton could have absolved him of his prior insubordination but chose not to. This says more about Shackleton's character as denying McNish his Polar Medal seems vindictive.

It is all too easy to criticize these actions when viewed 100 years later sitting in comfort."

I believe over 70 animals were on the Endurance- cat, dogs, and puppies.

@StyleCounselor:

But he only ordered the deaths of the cat and four dogs. Three of the dogs were noted as being puppies, and the fourth may have been as well. The rest of the dogs were probably used to help pull the lifeboats over the ice, earning their keep. What happens to them once the boats were all in the water, I don’t know. If any record exists of their fate, @FlagsNZ might know.

Endurance started the trip with 69 sled dogs and Mrs Chippy. During the trip a number of litters were born, I'm not sure how many pups there were.

None of the dogs survived. They barely had enough food to keep themselves alive, never mind all the dogs.

https://eshackleton.com/2016/01/14/death-was-instantaneous/

That page describes the first round, when 4 teams of dogs were killed. The others met the same fate.

@PurpleDave:

@Duq said:

"Endurance started the trip with 69 sled dogs and Mrs Chippy. During the trip a number of litters were born, I'm not sure how many pups there were.

None of the dogs survived. They barely had enough food to keep themselves alive, never mind all the dogs.

https://eshackleton.com/2016/01/14/death-was-instantaneous/

That page describes the first round, when 4 teams of dogs were killed. The others met the same fate."

That's what I figured. It sounds brutal. Yet, you wonder if that sort of horror got the message through completely to everyone exactly what they were in for and what sort of sacrifice would be required before people started dying.

In a life-or-death survival situation, that seems like a lot of valuable protein and warm fur that was wasted.